This is the ground breaking paper by Richard P. Feynman: 'Space-Time Approach to Quantum Electrodynamics'

To be honest, I can read such a paper as if it is a novel, written in French.

Now I cannot really speak French, but I can at least understand a bit of what

they are saying, if they are prepared to pronounce slowly. And that turns out

to be difficult: "Lentement, s'il vous plait, très lentement."

Well, everybody has his specialism. And Quantum ElectroDynamics (QED)

certainly is not mine. Why then this attempt to nevertheless say some

sensible things about it? To our great relief, the following sentence

appears in Feynman's paper, quote from chapter 5:

We desire to make a modification of quantum electrodynamics analogous to

the modification of classical [OK !] electrodynamics described in a previous

article, A. There the δ(s122) appearing in the

action of interaction was replaced by f(s122) where f(x)

is a function of small width and great height.

Further support of this idea is found in the very well readable

Richard P. Feynman - Nobel Lecture :

There were several suggestions for interesting modifications of electrodynamics. We discussed lots of them, but I shall report on only one. It was to replace this delta function in the interaction by another function, say, f(I2ij), which is not infinitely sharp. Instead of having the action occur only when the interval between the two charges is exactly zero, we would replace the delta function of I2 by a narrow peaked thing. Let's say that f(Z) is large only near Z=0 width of order a2. Interactions will now occur when T2-R2 is of order a2 roughly where T is the time difference and R is the separation of the charges. This might look like it disagrees with experience, but if a is some small distance, like 10-13 cm, it says that the time delay T in action is roughly √ (R2 ± a2) or approximately, - if R is much larger than a, T = R ± a2/2R. This means that the deviation of time T from the ideal theoretical time R of Maxwell, gets smaller and smaller, the further the pieces are apart. Therefore, all theories involving in analyzing generators, motors, etc., in fact, all of the tests of electrodynamics that were available in Maxwell's time, would be adequately satisfied if were 10-13 cm. If R is of the order of a centimeter this deviation in T is only 10-26 parts. So, it was possible, also, to change the theory in a simple manner and to still agree with all observations of classical electrodynamics. You have no clue of precisely what function to put in for f, but it was an interesting possibility to keep in mind when developing quantum electrodynamics.

It is noted that much of this classical

electrodynamics theory is also found in 'The Feynman Lectures on Physics'

Part II, chapter 28: 'Electromagnetic mass'. In paragraph 28-5, which is titled

'Attempts to modify the Maxwell theory' we read (at page 28-8) about 'another

modification of the laws of electrodynamics as proposed by Bopp'. Bopp's theory

is that: Aμ(1,t1) = ∫

jμ(2,t2) F(s122)

dV2 dt2

It's important to observe that the above integral has all characteristics

of a convolution integral with F as a kernel.You may forget all

the rest, but remember this !

Subsequent quotes are aimed at showing that Feynman actually did copy the

method "with δ replaced by a function of small width and great height",

from classical electrodynamics to quantum electrodynamics:

Anyway, it forced me to go back over all this and to convince myself physically

that nothing can go wrong. At any rate, the correction to mass was now finite,

proportional to ln(m.a/h) (where a is the width of that function f which was

substituted

for δ). If you wanted an unmodified electrodynamics, you would have to

take a equal to zero, getting an infinite mass correction. But, that wasn't the

point. Keeping a finite, I simply followed the program outlined by Professor

Bethe and showed how to calculate all the various things, the scatterings of

electrons from atoms without radiation, the shifts of levels and so forth,

calculating everything in terms of the experimental mass, and noting that the

results as Bethe suggested, were not sensitive to a in this form and even had

a definite limit as a → 0.

[ ... snip ... ]

It must be clearly understood that in all this work, I was representing the

conventional electrodynamics with retarded interaction, and not my halfadvanced

and half-retarded theory corresponding to (1). I merely use (1) to guess at

forms. And, one of the forms I guessed at corresponded to changing δ to

a function f of width a2, so that I could calculate finite results

for all of the problems. This brings me to the second thing that was missing

when I published the paper, an unresolved difficulty. With δ replaced by

f the calculations would give results which were not "unitary", that is, for

which the sum of the probabilities of all alternatives was not unity. The

deviation from unity was very small, in practice, if a was very small. In the

limit that I took a very tiny, it might not make any difference. And, so the

process of the renormalization could be made, you could calculate everything in

terms of the experimental mass and then take the limit and the apparent

difficulty that the unitary is violated temporarily seems to disappear.

I was unable to demonstrate that, as a matter of fact, it does.

That was in 1965. Since then, a zillion proposals have been done to get rid of the "infinities" in Quantum Electrodynamics. Shall we summarize the situation?

But, some people seemingly succeed in keeping sort of order in the chaos. People such as John Baez. He has written many lucid articles on Mathematical Physics, this one for example:

Renormalization Made Easy (but where is it?)

We are talking here about the "oldest game", which is Feynman's game. A rather new development is the approach via "renormalization groups" by Kenneth Wilson (1982). Giving rise, again, to an interesting quote:

Wilson's analysis takes just the opposite point of view, that any quantum field theory is defined fundamentally with a distance cutoff D that has some physical significance. In statistical mechanical applications, this distance scale is the atomic spacing. In quantum electrodynamics and other quantum field theories appropriate to elementary particle physics, the cutoff would have to be associated with some fundamental graininess of spacetime, [ ... snip ... ] But whatever this scale is, it lies far beyond the reach of present-day experiments. Wilson's arguments show that this this circumstance explains the renormalizability of quantum electrodynamics and other quantum field theories of particle interactions. [ ... snip ... ]

There is also a popularized version of Quantum ElectroDynamics theory:

Feynman's book

'QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter'.

The effects of Gaussian broadening may be visualized

as follows.

Work in Progress

Time to come to a summary. We find that the "oldest renormalization game" is

actually nothing else than the following. Point-like interaction, as formalized

by the presence of a delta-function in sort of a convolution integral, is being

replaced by interaction over a short distance, as formalized by the presence of

a "function f of small width and great height" in the same convolution integral.

The "width" of that function f is the infamous "cut-off" value in QED. Hence we

must work the other way around. Instead of considering a delta function as the

sharp (desirable) limiting shape of i.e. a Gaussian distribution, we must now

consider (for example) a Gauss distribution as the (desirable) broadening

of a delta function. Both kind of functions occur as the kernels in convolution

integrals. Where have we seen all of this before? When formulated in this way,

the situation in Quantum ElectroDynamics is by no way unique. You really don't

need elementary particles for being able to do fundamental research.

For the sake of clarity, any "function of small width and great height", which

converges to a delta-function as the width → 0, will be called a shape

function in the sequel. To be more precise: it's a shape function in the

sense of a Finite Volume Method. There is no confusion, actually, because the

shape functions in Numerical Analysis are a subclass of the shape functions in

our Fuzzy Analysis.

(This work is not perfect yet. Improvements have been suggested by Robert Low,

as seen in a subtread of 'Probability in an infinite sample space':

1 ,

2 ,

3 ,

4 ,

5 )

In the same document, a result is established

which is quite relevant here: Gaussian Smoothing is represented by an operator

exp( 1/2 σ2 d/dx2 )

But the theory of Fuzzyfied Logic, which is contained in the same

documentation &

software bundle, is even more appropriate for this application.

Here is a visualization of the fuzzyfied equality, as a

function of x and y, according to the latter theory.

The Top Down Approach

The Discrete finds its origin in Mathematics itself. Originally, it has been

associated with the art of

counting. Not so with the Continuum. The continuum finds its origin in

measurements, especially in Geometry, hence in Physics. There is some truth

in Newton's remark "for the description of right lines and circles, upon

which geometry is founded, belongs to mechanics", as quoted from: Preface

to Isaac Newton's Principia (1687). Pure mechanics is thus really very close to pure

mathematics: kinematics = geometry + time , dynamics = kinematics + mass .

Anyway, the continuum has as its main characteristic that it is not countable,

but measurable (in a physical sense).

We can conclude that the Discrete is Bottom-Up (accessible through counting)

while the Continuous is Top-Down (accessible through measuring). We can see,

however, that some top-down techniques can also be associated with discrete

things, like paying with Euro's. The reverse is

also true: the continuum can be discretized and hence made accessible

through counting (maybe accounting: bookkeeping). That's what Numerical

Analysis is all about. It turns out that the problem of the Continuum,

there, is not so much in continuity as such, but merely in its relationship to

the Discrete.

As opposed to Discretization, how about Continuization ? What if not only top-down methods can be employed with the discrete, but even the discrete itself can be made continuous ? In fact, this is what actually happens with our Numerical Methods, as soon as discrete points are associated with so-called Shape Functions, in order to enable differentiation and integration. The latter being actions which are typically in the need of a continuous (and even analytical) domain. Finite element shape functions (or rather interpolations) are among the most elementary examples of functions which can be employed for the purpose of making a discrete substrate continuous (again). But there are others, like the bell shaped Gaussian curves, employed with Fuzzy Analysis. We have already decided to use the same name for these and for the shape functions in Numerical Analysis as well. I think what Applied needs is no more discretization, but continuization instead ;-)

An interesting pattern is emerging now. It is known that a continuous function can be discretized (sampled) by convoluting it with a comb of delta-functions. (Examples are in 'Discrete Linear System Summary' & 'Aliasing, Image Sampling and Reconstruction') But we have also seen the reverse now: a discrete function can be made continuous by convoluting it with a comb of shape functions. This is commonly called 'interpolation'. However, if Gaussian distribution functions are being employed as interpolants, then the discrete function values are actually a bit different from the continuized function values at the same place. Summarizing:

Our top down approach may also be called AfterMath :-).

It's After the Mathematics. Post-processing instead of pre-processing.

The taste of the pudding is in the eating. The crucial question is: whether

(renormalization = continuization = Gaussian broadening) according to this

author (HdB) is indeed capable of removing singularities. Due to the

limitations of HTML, two PDF documents have been produced on this issue:

The sources of the first document and (Delphi Pascal) test programs are

included as well. Here are some results, for the

2-D and for the 3-D case

respectively.

A typical example is the ideal gas law: p = c.T/V , where p = pressure,

V = volume, c = constant, at a constant temperature T. No matter how you try,

it's impossible to renormalize the function p(V) for V → 0 . This

is due to the one-dimensional character of it. But, as everybody knows,

nature has found a solution for the zero Volume problem: the ideal gas law is

changed into something else, another law of nature. The gas becomes a

fluid. And, under even more pressure, the fluid becomes a solid.

But, uhm .. on retrospect, it seems that my approach has been more difficult

than necessary. A function 1/r in 2-D

may be simply renormalized

as 1/√(r2 + σ2) and a function

1/r2 in 3-D

may be simply renormalized as

1/(r2 + σ2) : a Cauchy distribution

for the latter. The smaller σ is, the "better". Green lines in the

pictures.

Three additional publications:

But other name calling comes into mind as well. Smoothening can be considered

as the modelling of a measurement process. The mathematical phenomenon is

"sensed", so to speak, with a physical device, a sensor. Sensors always

come with a spread σ , kind of a limited aperture, sort of fuzzyness,

which makes any measurement vulnerable to a certain uncertainty. The common

philosophy still is that these errors are not part of nature itself, but only

part of our methods of observing it. But, according to

Quantum Mechanics, "our" observations are part of the

observed phenomenon itself ! Worse, it's not "us" who are observing nature.

Nature is observing itself, with "us" as a medium, eventually. But not

necessarily. It's no miracle that the electron observes it's own self energy

(the name says it) by sending virtual photons back and forth to itself. It

has a built-in sensor. Thus the sensor, the smoothening kernel, is part of

the physical modelling, even in theory. It may be universal, so let's call it

the Cosmic Sensor eventually. (Not to be confused with "Cosmic Censor" in

the Cosmic

Censorship hypothesis.)

Renormalization of

Singularities

The core activity of renormalization is the calculation of a convolution

integral with a shape function as a kernel. But, with the evaluation of these

integrals, it makes a huge difference whether you integrate in one (dx),

two (dx.dy) or three (dx.dy.dz) dimensions. So the dimensionality (1,2,3,4,..)

is crucial with the successful continuization - yes or no - of singularities.

This argument is, however, misleading. Simplified renormalizations

can only be substituted iff it has been firmly established that the

original functions indeed get lost of their singularities with (the model of)

some measurement. That is: the convolution with a shape function always comes

first, simplification may come afterwards.

Fluid Tube Continuum

One of the most striking examples of Continuization has been the discovery of

the so-called Fluid-Tube Continuum. Well, it's been a long story. At that time,

an international (European) consortium was working on the infamous fast breeder

nuclear reactor in

Kalkar (West Germany).

The Dutch partner in this consortium was called

Neratoom. As an

employee of Neratoom, I have mainly been working on both

sodium

pumps

and the

IHX

(intermediate heat exchanger). It was the

Numerical Analysis of the latter apparatus that has led us to the

Fluid Tube Continuum.

The idea behind this comes from the classical theory of Porous Media.

It is virtually impossible, namely, to apply the original Navier-Stokes / Heat

Transfer equations, together with their boundary conditions, to a truly

detailed model of the tube bundle. With help of the porous media theory,

though, it can be argued that the flow field, as a first approximation, is

irrotational. Furthermore, the liquid (sodium) is incompressible and it

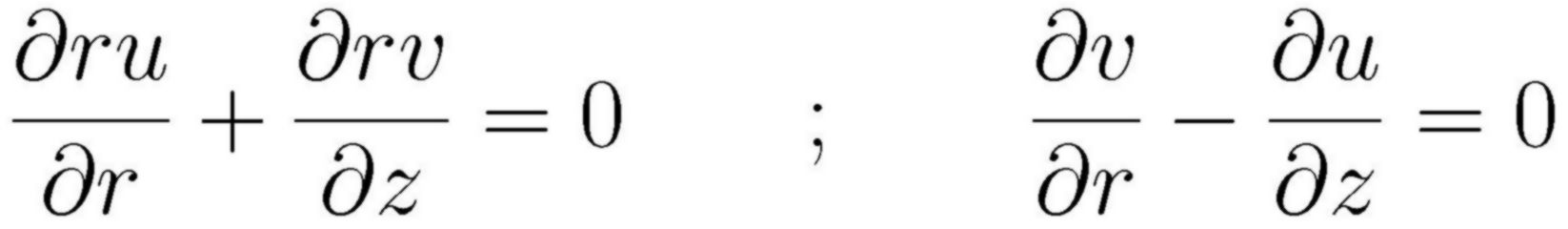

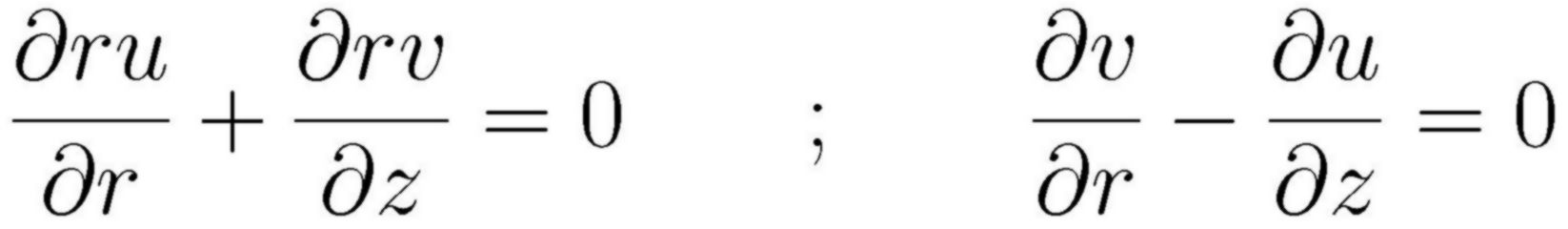

is contained in a cylinder symmetrical geometry. Such an example of Ideal

Flow is described by the following system of first order PDE's (Partial

Differential Equations):

|

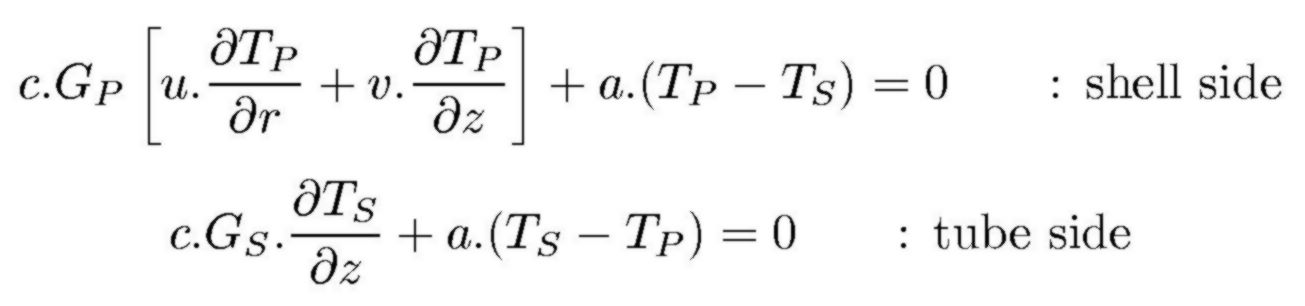

These PDE's have been solved numerically. To that end, the same discretization method as with another ideal flow problem (Labrujère's Problem) has been employed. With help of the fluid tube continuum model, as a next step, the partial differential equations for the primary and secondary temperatures (heat balances) are set up:

|

Having calculated the flow field, the PDE's for the temperature fields have to be solved too. To that end, several methods - none of them very revolutionary - have been employed. The resulting computer program, which calculates both the flow and the temperature fields and compares the latter with real experiments, is in the public domain. Further interesting details are found in a SUNA publication. Especially the statement that the assumption of Ideal Flow also gives rise to a higher safety margin with respect to the temperature stresses deserves attention. A neater representation of the proof hereof is disclosed too.

But the most interesting is that quite unexpected things may happen at the

boundary between the Continuous and the Discrete! BTW, a Dutch version

of the previous has been available for a couple of years ( > 1995); it's

section 6.7 in my book. The

Fluid Tube Continuum has as a tremendous advantage that the granularity

of its discrete substrate is known: it is the pitch of the tube bundle.

It is shown in the

paper

how this continuum breaks down for a certain critical primary mass flow,

which so large, namely, that the heat can no longer be transferred within the

distance of a pitch.

What relationship does there exist between a fluid tube continuum and the

Prime Number Theorem ? Well, according to the prime number theorem,

the (approximate) density of the prime numbers in the neighbourhood of a number

x goes like 1/ln(x) . But, in order to be able to speak of a density,

prime numbers must be subject to, yes: continuization. Like with the

tube bundle of a heat exchanger, discrete items (tubes / primes) must be

blurred, in such a way that things are not visible anymore as separate

objects. In order to accomplish this, the same technology as with numerical differentiation might be employed:

P(x) = Σk fk

e-[(x - xk) / σk]2 / 2

with discrete values fk

at positions xk

σk = √ xk . ln( xk )

(according to an estimate by von Koch)

Indeed, with these spreads, it turns out that the density distribution P(x)

of the prime numbers is approximated very well by the theoretical result:

1/ ln(x) .

Prime Number Theory

Here the spread σ, too, has been made dependent on k . Now make all

function values fk equal to 1 . And next identify the positions

xk with the prime number positions. Then only the following

question remains. What values must be designated to the spreads

σk , in order to accomplish that the series P(x) represents

a (n almost) continuous function ? Don't expect my contributions to

Prime Number Theory to be of the same level as those to Numerical Analysis (?)

But, nevertheless, I want to coin up my 5 cents worth, being the following

conjecture:

According to R.C. Vaughan (February 1990): It is evident that

the primes are randomly distributed but, unfortunately, we don't know what

'random' means.

This is Experiment number 4 in the accompanying software,

where the primes are

replaced by random hits in a Monte Carlo experiment. And very well indeed, the

abovementioned spread σk does not seem to be typical

for prime numbers only !