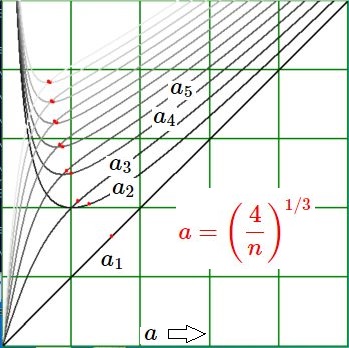

Thirteen functions $a_k(a)$ with $k = 1,2,\cdots ,13$ are displayed; lower iterands with darker lines.

The viewport is:

xmin = 0; xmax = 5; ymin = 0; ymax = 5;Let's make a few calculations, for the sake of understanding the graphics: $$ a_1(a) = a\\ a_2(a) = \frac{a^2+1}{a}\\ a_3(a) = \frac{a(a^2+3)}{a^2+1}\\ a_4(a) = \frac{a^4+6a^2+3}{a(a^2+3)}\\ a_5(a) = \frac{a(a^4+10a^2+15}{a^4+6a^2+3} $$ That's enough to see the folowing fact:

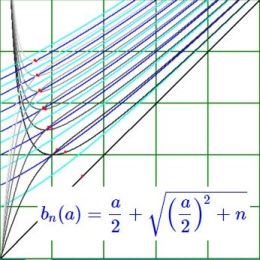

EDIT. In order to solve for the points of intersection, equate $a_{n+1}$ to $a_n$ , noticing that $a_n > 0$ : $$ a_n = a_{n+1} = a + \frac{n}{a_n} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a_n^2-a\cdot a_n-n = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a_n = \frac{a}{2} + \sqrt{\left(\frac{a}{2}\right)^2+n} $$ So now we know the ordinates of the intersection points. But, unfortunately, that doesn't give us any information about the abscissas $a$. What we can do is draw the $\color{blue}{\mbox{graphs}}$ of the new functions, name them $b_n(a)$ :

We expect that $b_n(a) = a_n(a) = a_{n+1}(a)$ at the intersection points. However, there is a difference between the curves in dark Blue and light blue (Aqua). The former are for $b_n(a)$ with $n = $ even; they intersect $a_n(a)$ and $a_{n+1}(a)$ as expected. The latter are for $b_n(a)$ with $n = $ odd; they do not intersect $a_n(a)$ and $a_{n+1}(a)$. But all blue curves $b_n(a)$ are somehow interesting, because they are asymptotes to the curves $a_n(a)$. For large values of $a$ we have almost straight lines: $$ b_n(a) = \frac{a}{2}+\frac{a}{2}\sqrt{1+\frac{n}{(a/2)^2}} \approx a + \frac{n}{a} $$ Still another way to calculate the intersection points is to determine the minimum of the curves $a_n(a)$ for $n = $ even. Which is easy to prove, because $a_n(a)\ne a/2$ in : $$ a_n^2(a)-a\cdot a_n(a)-n = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a_n'(a)\left[2 a_n(a)-a\right]= 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a_n'(a)=0 $$ The slope of the accompanying odd curve at such a minimum is always $1$ , according to: $$ a_{n+1}'(a) = \left(a-\frac{n}{a_n(a)}\right)' = 1-\frac{n\, a_n'(a)}{a_n^2(a)} = 1 $$ Let's do some work with help of MAPLE:

\> a_1 := a; a_2 := a+1/a_1; a_3 := a+2/a_2; a_4 := a+3/a_3; a_5 := a+4/a_4;Though I find it not very enlightning, in this case an exact solution can be found as well: $$ a_{4,5} = \sqrt{\left(8+6\sqrt{2}\right)^{1/3}-\frac{2}{\left(8+6\sqrt{2}\right)^{1/3}}-1}; $$ Continuing in this way (with some higher precision) gives the following results, before MAPLE and my own Newton-Raphson iterations give up. $$ \begin{matrix} {\bf \mbox{IP abscisssa} \; a} & {\bf n} & {\bf < 4/a^3} \\ 1 & 2,3 & 4 \\ 0.871337913570159 & 4,5 & 6.04644570004055 \\ 0.792253607266638 & 6,7 & 8.04391208677473 \\ 0.736268951824715 & 8,9 & 10.0219107501819 \\ 0.693502616556087 & 10,11 & 11.9926643644897 \\ 0.659225892899425 & 12,13 & 13.9623081896349 \\ 0.630825547822963 & 14,15 & 15.9342699607407 \\ 0.606713039185383 & 16,17 & 17.9105946558336 \end{matrix} $$ Herewith the conjecture is proved , for $\;n=1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17$ .

\> fsolve(a_4=a_5,a,0..infinity);

0.8713379136

\> fsolve(a_4=a/2+sqrt((a/2)^2+4),a,0..infinity);

0.8713379136

\> fsolve(diff(a_4,a)=0,a,0..infinity);

0.8713379136

\> subs(a=%,a_4);

2.482570870

POST BOUNTY. Geromty's conjecture has been proved now (numerically) for $n$ up to $10,000$ . The only limitation seems to be that one has to halt at some place. Our last line of output has been: $$ \begin{matrix} {\bf \mbox{IP abscisssa} \; a} & {\bf n} & {\bf < 4/a^3} \\ 0.0564535548737650 & 9998,9999 & 22232.3877129834 \end{matrix} $$ It is thus noticed that geromty's formula gives over-estimates by more than a factor $2$ for such large values of $n$ , that is: if our calculations can be trusted. If one is truly interested in a lower bound for $n$ such that $\,a_{n+1} > a_n$ , then one could think about employing the little computer program below, instead of the conjecture. Here is the (Pascal) source code of the executable that does the job:

program maple;I leave it up to the interested user to figure out the inner workings of this little program. Especially note that the quotient of $a_n(a)$ and its derivative $a_n'(a)$ can be calculated iteratively, in one sweep.

function quotient(n : integer; a : double) : double; { a_n(x)/a_n'(x) } var x,y : double; k : integer; begin y := a; x := 1; for k := 1 to n-1 do begin x := 1 - k\*x/sqr(y); y := a + k/y; end; quotient := (a + n/y - y)/(1 - n\*x/sqr(y) - x); end;

procedure main(M : integer; var a : double); { Newton-Raphson algorithm } var x,y : double; begin x := a; while true do begin y := x; x := x - quotient(M,x); if abs(y - x) < 1.E-12 then Break; end; a := x; end;

procedure test(M : integer); var a,vgl : double; k : integer; begin a := 1; for k := 2 to M do begin main(2\*k,a); vgl := 4/(a\*a\*a); Writeln(a,' ',2\*k,',',2\*k+1,' ',vgl); end; end;

begin test(4999); end.

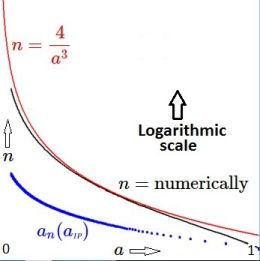

Upon request: A graph showing the (numerically obtained) intersection points (abscissas) as a function of $n$ would be nice :) But instead, here comes a graph of ( the natural logarithm of ) the number of iterations $n$ as a function of the abscissas $a$ of the intersection points, where $0 < a < 1$ and $0 < \ln(n) < 15$ . And $10,000$ intersection points have been taken into account.