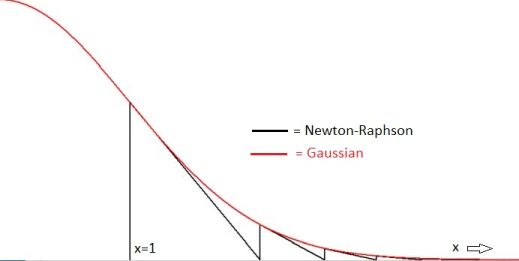

But suppose that we modify the problem a bit, as follows: find the zeroes of $\;f(x) = e^{-x^2/2} - e^{-N}\;$ with $N$ some large positive integer, then we have instead the sequence: $$ x_{n+1}=x_{n}+\frac{1}{x_n}\left[1-\frac{e^{-N}}{e^{-x_n^2/2}}\right] $$ And now the iterations stop when: $$ x_{n+1} = x_n \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad e^{-x_n^2/2} = e^{-N} \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad x_n = \sqrt{2N} $$ Here is a little (Delphi Pascal) program that does the job:

program Diego;Output:

procedure main(N : integer); var x,y : double; t : integer; begin Writeln('sqrt(2N) =',sqrt(2\*N)); x := 1; y := 0; t := 0; Writeln(t:4,' : x =',x); while not (y=x) do begin y := x; t := t + 1; x := x + 1/x\*(1-exp(-N)/exp(-sqr(x)/2)); Writeln(t:4,' : x =',x); end; end;

begin main(8); end.

sqrt(2N) = 4.00000000000000E+0000 0 : x = 1.00000000000000E+0000 1 : x = 1.99944691562985E+0000 2 : x = 2.49834687643857E+0000 3 : x = 2.89556809260418E+0000 4 : x = 3.23325795454623E+0000 5 : x = 3.52322153181656E+0000 6 : x = 3.75982762597611E+0000 7 : x = 3.92105171808397E+0000 8 : x = 3.98953172402065E+0000 9 : x = 3.99979758749457E+0000 10 : x = 3.99999992320208E+0000 11 : x = 3.99999999999999E+0000 12 : x = 4.00000000000000E+0000 13 : x = 4.00000000000000E+0000So far so good. Now, what will happen if the value of $N$ is increased indefinitely? Then the sequence will become longer and longer; in the end it will never stop. Moreover, the following will be true: $$ \lim_{N\to\infty} e^{-N} = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad x_{n+1}=x_{n}+\frac{1}{x_n} $$ It is clearly seen, however, that the number of iterations in the finite case ($n = 13$) does not equal $N = 8$ . So I doubt if the conjectured limit is true. Still apart from the fact that subtraction of two (infinitely) large numbers is highly unstable numerically (i.e. "bad" limit).

Update. Further numerical experiments reveal that indeed our iterands $\,x_n\,$ as well as the OP's original $\,a_n\,$ are close to $\,\sqrt{2n}\,$ and the larger $\,n\,$ the better, it seems. Here is an example, with $\,\sqrt{2\times 8192} = 128$ :

8188 : x = 1.27991318734407E+0002 , a = 1.27993080007178E+0002 8189 : x = 1.27996559906482E+0002 , a = 1.28000892929564E+0002 8190 : x = 1.27999342587009E+0002 , a = 1.28008705375065E+0002 8191 : x = 1.27999973101217E+0002 , a = 1.28016517343767E+0002 8192 : x = 1.27999999953749E+0002 , a = 1.28024328835758E+0002 <== 8193 : x = 1.27999999999999E+0002 , a = 1.28032139851126E+0002 8194 : x = 1.28000000000000E+0002 , a = 1.28039950389958E+0002 8195 : x = 1.28000000000000E+0002 , a = 1.28047760452340E+0002So it may be conjectured that for all $\,n$ : $$ x_n < \sqrt{2n} < a_n $$ With: $$ x_{n+1} = x_n + \frac{1}{x_n}\left[1 - \frac{e^{-n}}{e^{-x_n^2/2}}\right] \quad ; \quad a_{n+1} = a_n + \frac{1}{a_n} $$ I have not (yet) been able to prove that this conjecture is true.

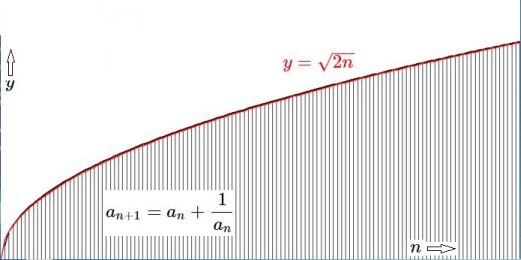

Then consider the following sequence. Fasten your seatbelts!

$$

a_{n+1} = a_n + \frac{1}{a_n} \\

\frac{a_{n+1} - a_n}{1} = \frac{1}{a_n} \\

\frac{a(n+dn) - a(n)}{dn} = \frac{1}{a(n)} \\

a'(n)\,a(n) = 1 \\ \frac{da^2(n)}{dn} = 2 \\

a^2(n) = 2n+C

$$

[Scaling argument deleted. I see no way to get it consistent, let it be rigorous. See edits of this post]

Now we would like to have $\,C=0$ ; and fortunately there is a boundary condition, for $\,n=2$ , that fits the bill : $\,C = a_2^2 - 2\cdot 2 = 0$ . So:

$\;a_n = \sqrt{2n}$ .

The larger $n$ , the better all of the approximations. A much neater way to express the end-result is:

$$

\large \boxed{\lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{a_n}{\sqrt{2n}} = 1}

$$

BONUS. Lemma:

$$

a_{n+1} = a_n + \frac{1}{a_n} \quad \Longrightarrow \quad

a_{n-1}^2 - a_na_{n-1} + 1 = 0 \quad \Longrightarrow \quad a_{n-1} = \frac{a_n}{2} + \sqrt{\left(\frac{a_n}{2}\right)^2-1}

$$

Now compute (the discretization of) the second derivative, assuming again that $\,a_n\,$ is large:

$$

a''(n) = a_{n+1} - 2a_n + a_{n-1} = a_n + \frac{1}{a_n} - 2a_n + \frac{a_n}{2} +

\frac{a_n}{2}\sqrt{1-\frac{1}{(a_n/2)^2}} \approx \\ \frac{1}{a_n} - \frac{a_n}{2} + \frac{a_n}{2}

\left[1-\frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{(a_n/2)^2} - \frac{1}{8}\left(\frac{1}{(a_n/2)^2}\right)^2\right] = -\frac{1}{a_n^3}

$$

Which means that the discrete function $\,a_n\,$ for large $\,n\,$ is actually very smooth , when seen as a continuous

and differentiable $\,a(n)$ . This is an even stronger motivation for the above treatment.

It is noticed that the "true" derivatives exhibit the same structure as the discretizations:

$$

\left(\sqrt{2x}\right)'' = \left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2x}}\right)' = -\frac{1}{\left(\sqrt{2x}\right)^3}

$$

There are no coincidences in mathematics.