An “isomorphism” between continuous and discrete mathematics

The objective of this answer is to show that, contrary to the common paradigm in Physics,

discrete models are more informative than continuous models. The Discrete is "nearer to the truth",

so to speak, than the Continuous. Where it is supposed, of course, that the Continuous and the Discrete

are just two different means of looking at the same physical phenomenon. We shall motivate our

(perhaps somewhat exaggerated) point of view at hand of two examples.

Longitudinal Waves

MSE reference:

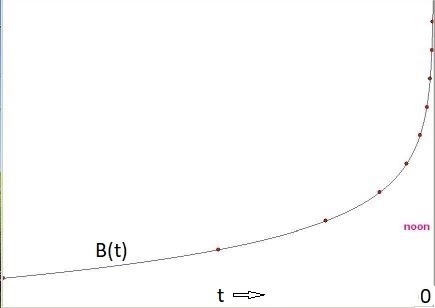

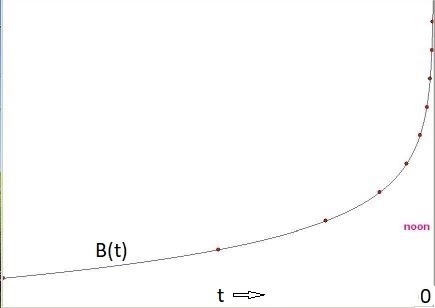

The main picture from Question & Answer is copied here for convenience:

Where it is clearly suggested that the black dots are the Discrete / longitudinal wave, and the sinusoidal curve is the

Continuous / transverse wave.

Now the following fact is proved in the above Q&A reference. Let $\;\lambda\;$ be the wavelength of the longitudinal

wave and $\;A\;$ its amplitude. Then, independent of any discretization we have:

$$

A < \frac{\lambda}{2\pi}

$$

Most astonishing is that I have never encountered this restriction anywhere in literature. But apart from this,

it is clear that the restriction only comes from the Discrete underpinning the continuous. It cannot be derived

from the continuous model alone (i.e transverse wave) that an amplitude may be limited by the wavelength.

Upwind Schemes

MSE reference:

The following is from the famous

book

by S.V. Patankar: Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow; Hemisphere Publishing Company U.S.A. 1980 (page 84).

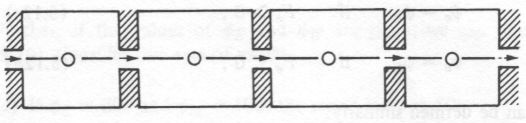

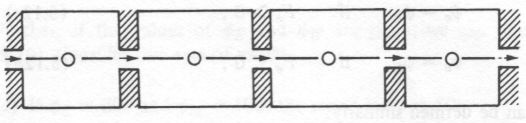

The scheme is sometimes said to be based on the "tank-and-tube" model (Gosman,

Pun, Runchal, Spalding, and Wolfshtein, 1969). As shown in Fig. 5.2 [below], the

control volumes can be thought to be stirred tanks that are connected in series

by short tubes. The flow through the tubes represents convection, while the

conduction through the tank walls represents diffusion. Since the tanks are

stirred, each contains a uniform temperature fluid. Then, it is appropriate to

suppose that the fluid flowing in each connecting tube has the temperature that

prevails in the tank on the upstream side. Normally, the fluid in the tube

would not know anything about the tank toward which it is heading, but would

carry the full legacy of the tank from which it has come. This is the essence

of the upwind scheme.

Especially take notice of the phrase: the fluid in the tube would not know anything about

the tank toward which it is heading, but would carry the full legacy of the tank

from which it has come. With other words, the upwind scheme is equipped with

"knowledge" about past and future. In the continuous analogue, on the contrary, the so-called

arrow of time is completely absent. Thus, when taking the limit for tank and tube sizes to zero,

directional information is lost forever. Therefore in the upwind case, the Continuous, instead

of the better and the more exact, rather seems to be sort of sloppyfication of the Discrete.

It is demonstrated in the same

MSE reference that upwind schemes are no way less accurate than, for example, central differences.

It's even possible to reproduce "exact" (read: analytical) solutions with them. So the argument that upwind schemes

are only $O(h)$ instead of $O(h^2)$ is just ge-$O(h)$, as we would say it

in good old Dutch :-)

The following question is copied from an old

thread

in sci.math

Suppose you have a giant vase and a bunch of ping pong balls with an

integer written on each one, e.g. just like the lottery, so the balls

are numbered 1, 2, 3, ... and so on. At one minute to noon you put

balls 1 to 10 in the vase and take out number 1. At half a minute to

noon you put balls 11 - 20 in the vase and take out number 2. At one

quarter minute to noon you put balls 21 - 30 in the vase and take out

number 3. Continue in this fashion. Obviously this is physically

impossible, but you get the idea. Now the question is this: At noon,

how many ping pong balls are in the vase?

The answer given by most mathematicians sounds as follows:

> Every ball placed into the vase (at a well-defined time before noon)

is taken out from the vase (at a later, well-defined time before noon).

Therefore at noon the vase is empty, there are no balls in the vase at noon.

However, we can say that the number of balls $\;B_k\;$ at step $\;k=1,2,3,4,\cdots\;$ is:

$$

B_k=B(t_k) = 9 +\, ^2\log(-1/t_k) \quad \mbox{where} \quad t_k = -1/2^{k-1}

$$

And if we properly interpolate these values, then we have a continuous

function that does not have the following limit:

$$

\lim_{t\to 0} B(t) = \lim_{t\to 0} \left[ 9 +\, ^2\log(-1/t) \right] = 0

$$

So (according to standard mathematics) the discrete is not isomorphic to the continuous at noon.