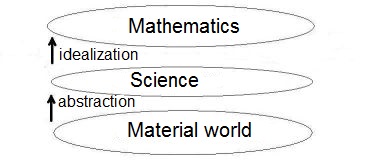

We would like to conjecture that two important mechanisms are involved

with a mathematical description of the material world:

- Abstraction, giving rise to Science

- Idealization, giving rise to Mathematics

Schematically:

Abstraction

Etymology. Perfect passive participle of abstraho ("draw away

from"). Certain properties of the whole thing are preserved in the process

of Abstraction:

We shall argue that Abstraction is not a mathematical but rather a physical

activity. It's already done by our senses. Our eyes can see the light, as it

is casted back from a piece of paper. The same piece of paper can be felt by

our fingertips. And when it is crumpled up, the sound of it will be heard by

our ears. But eyes cannot hear sound, fingertips cannot see light. All these

single perceptions of our senses have to work together. And even if we are not

handicapped, the end-result is still an abstraction of reality as a whole, a

part of it. None of our senses is capable, for example, to see ultraviolet

colors, as some insects probably can.

But why should attention be restricted to the creations of Nature? Why not

take a look at our own creations: human made Technology? Some cameras

are capable to "see" in the infrared domain. Our radio telescopes are even

capable to "see" the radio frequencies of far away galaxies. Far more common

and well-known everyday abstractions of reality are performed, however, with

measuring devices like rods for the abstraction of lengths, clocks for the

abstraction of time intervals. But these measuring devices have become more

and more self supporting these days. When coupled with digital computers, human

interaction is hardly needed anymore. All such apparatus make an abstraction of reality,

which is thus a physical and not a mental process.

Idealization

This raises an obvious question: where does"real" mathematics start

then? Answer: with the next step: Idealization. Idealization could

be characterized as the true mathematical activity. Idealization is where

imagination and phantasy come in. And it turns out that infinity

is often a keyword accompanying this process.

Many challenging idealizations are found in theories of Physics.

In "The Theory of Heat Radiation" by Max Planck, Wien's Displacement Law

(chapter III) can only be derived under the following conditions: if the black

radiation contained in a perfectly evacuated cavity with perfectly reflecting

walls is compressed or expanded adiabatically and infinitely slowly. Idealized

Carnot engines are used in Thermodynamics for defining that stunning but

indispensable quantity, called Entropy. And the list goes on and on. How about

ideal, frictionless movement in mechanics? How about ideal pendulums, which can

only exist through a sine with (almost) zero amplitude. As soon as physicists

have devised their mathematical model, then it can be said that idealization

has been accomplished a great deal. One should become alerted as soon as the

following phrases are being uttered: "perfect", "ideal", "zero", but especially

"infinitely", like in "infinitely slow" or "infinitely thin". It can safely be

concluded that Infinities are invariably associated with Idealizations.

Concerning mathematics,

among the most classical examples of idealization, without doubt, is good old

Euclidean Geometry - where we should start to consider geometry in its

original setting: classical Greek philosophy. Remember utterings like: a point

has no size, a line is infinitely thin, parallel lines intersect at infinity.

The concept of an irrational number wouldn't have emerged if Euclidean

geometry hadn't been there in the first place.

So what is $\sqrt{2}$ ? It's an idealization. It's an idealization of numerous

abstractions, abstractions of numbers like $1.414213562373$ or $1.14$ or $99/70$ ,

as measured for example with a rod when trying to determine the length of

the hypotenuse of a right triangle with legs of length $1$ meters.

$\sqrt{2}$ doesn't exist in the real world. But neither does an ideal triangle.

All you can have in reality is "wooden triangles with legs not exactly $1$ meters and a

main angle not exactly right".

A mathematics with such triangles would be

extremely clumsy, so we are happy that idealized triangles can be imagined.

It may be concluded that your "fixed length" is an idealization, an illusion

as well. This resolves the "paradox" that a "fixed length" could not be

represented by the infinitely many decimals of an irrational number. Both

the length and the number are not real.